Civil forfeiture is perhaps the newest tool in the fight against corruption in Ukraine. Its key idea is to deprive the rights to property of public servants who could not prove the legality of obtaining it.

Let's find out which challenges arise when hearing civil forfeiture cases.

Civil forfeiture: from idea to implementation

In Ukraine, cases of civil forfeiture are heard by the High Anti-Corruption Court, and the lawsuit to recognize assets as unfounded is filed by the prosecutors of the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor's Office and the Prosecutor General's Office. But the path to the sustainability of such a procedure was long.

In general, the basis for civil forfeiture is laid down in a number of international treaties, in particular, Article 20 of the Council of Europe Criminal Law Convention on Corruption, Article 54 of the UN Convention against Corruption, and others. The legitimacy of such an instrument in the context of deprivation of property rights was also confirmed by the European Court of Human Rights.

In 2015, the Verkhovna Rada adopted Law No.198-VIII, which for the first time in Ukraine allowed the forfeiture of unjustified assets of officials on a civil basis. But this mechanism was “curtailed” because it was used only after the conviction of a person for crimes and did not become widespread at all.

One of the impetuses for changes to the civil forfeiture procedure was the decision of the Constitutional Court of Ukraine dated February 26, 2019, on the recognition of Article 368-2 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (CC of Ukraine) on illicit enrichment as unconstitutional.

The decision emphasized that countering corruption in Ukraine is a task of exceptional social and national importance, and the criminalization of illicit enrichment is an important legal means of implementing state policy in this area. When defining such an act as illicit enrichment as a crime, it is necessary to consider the constitutional provisions that establish the principles of legal liability, human and civil rights and freedoms, as well as their guarantees.

That is why in 2019, the Verkhovna Rada adopted Law No.263-IX, which, in addition to restoring criminal liability for illicit enrichment (considering the conclusions of the CCU), introduced an updated mechanism of civil forfeiture, which does not require the conviction of a person to confiscate unjustified assets. However, most of the comments in the course of its development were either ignored or left to the discretion of the court and prosecutors. This gave rise to some difficulties both in theory and in practice in the application of civil forfeiture of unjustified assets.

Rules to recognize assets as unjustified

The updated model of recognizing assets (income from them) as unjustified has become a tool for depriving a person of assets that do not correspond to their legitimate income. Under this approach, the state assumes the illicit acquisition of such assets, but does not prove their specific methods of obtaining, and such confiscation applies only to property associated with officials.

A key feature of civil forfeiture is the absence of the need to establish the guilt of a person in committing an offense, as a result of which they obtained certain assets. In such cases, the use of criminal law mechanisms to counter corruption is not always justified and is complicated by the high latency (concealment) of corruption. Because if an official nevertheless received some “kickbacks” or unlawful advantage, and this was ignored by law enforcement agencies, or it happened with their assistance, it is not always easy to prove in court the fact of committing such a criminal offense.

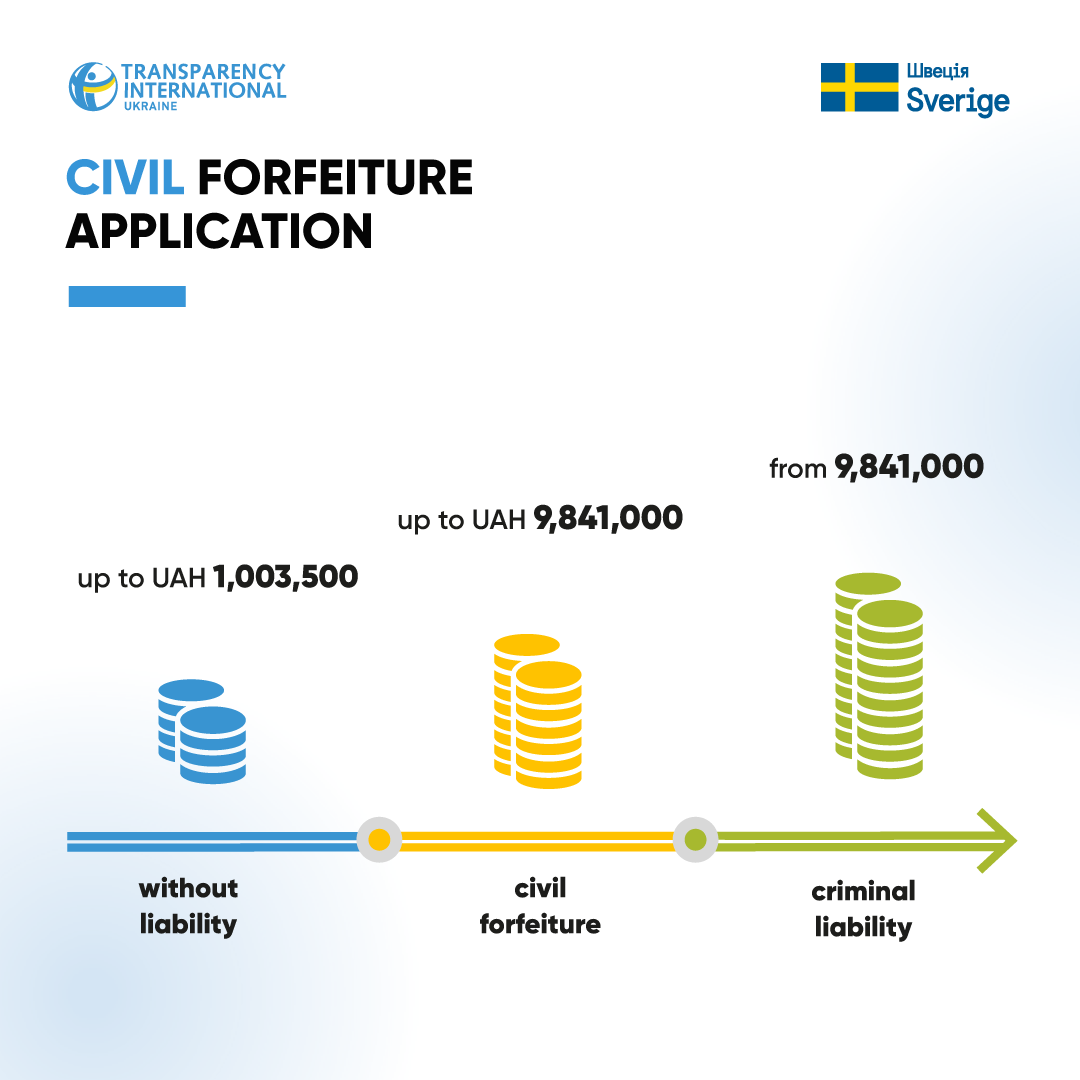

The application of civil forfeiture in accordance with Art. 290, part 2 of the Civil Procedural Code of Ukraine (CPC of Ukraine) is possible if the value of assets varies from 500 subsistence minimums as of the date of entry into force of the law, which is UAH 1,003,500, to 6,500 non-taxable minimum incomes of citizens (as of January 1, 2024, this is UAH 9,841,000).

Going beyond this higher threshold already leads to criminal liability under Art. 368-5 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine (unlawful enrichment).

In its content, civil and criminal cases on unjustified assets concern the solution of identical situations: the acquisition by an official of assets or income derived from them, which obviously do not correspond to their legitimate income. However, the resolution procedure is radically different.

For example, the head of the AMCU is accused of illicit enrichment. As the head of the Donetsk Regional State Administration, he allegedly acquired 21 real estate objects and a luxury car, registering the property to his wife's relatives. This entails illicit enrichment because the difference between the value of the specified property and the funds of the official and his wife amounted to UAH 56.2 million. In regard to the assets of the head of Vinnytsia United City Territorial Center for Recruitment and Social Support, the civil forfeiture procedure was applied as he had illegally acquired an apartment worth UAH 1.2 million.

Therefore, civil forfeiture allows, without convicting a person “beyond reasonable doubt,” to quickly and effectively deprive an official of the property that he/she acquired for illegal income. The standard of proof “beyond reasonable doubt” means that the totality of the circumstances of the case established during the trial excludes any other reasonable explanation of the event that is the subject of the trial, besides the fact that the charged crime was committed, and the accused is guilty of committing it. In civil forfeiture, another standard is used—“preponderance of evidence,” which we will cover in more detail further.

To initiate a lawsuit, the prosecutor of the SAPO or the PGO (in the case of acquisition of unjustified assets by an employee of the SAPO or the NABU) collects the evidence base and forms a civil lawsuit against the official who allegedly acquired unjustified assets. The HACC hears these cases within civil proceedings.

Interestingly, the case is heard not against the person (in personam), but against their property (in rem). That is, it is not the actions of the person that are assessed in regard to forfeiture, but the insufficiency of legal income to obtain the assets. The owner plays a secondary role here.

When resolving such a case, the court must find out the answers to a number of questions.

- Does the value of the asset meet the thresholds?

- Was the asset acquired after the law came into force?

- Is the defendant a person authorized to perform the functions of the state or local self-government?

- Is there a connection between the official and the asset?

- Is it possible to establish from the evidence that the official had sufficient legal income to acquire these assets?

At the same time, according to civil law, there is a presumption of legitimacy of the acquisition of property rights. But in this category of cases, the HACC formulated a position on the “presumption of the unjustified nature of assets.” The court applies it as follows: if the origin of the funds for the acquisition of the asset remains unknown, the court cannot conclude on the legality of the sources of these funds. That is, from the very beginning, there is a greater probability that the asset is unjustified, until the defendant refutes this, proving the legality of this property.

Difficulties in adopting a law on civil forfeiture

The development and adoption of the draft law on civil forfeiture was very controversial, as the original version offered some “know-how” in which many institutions saw serious risks.

Thus, the first version proposed to extend its effect to assets acquired within four years before the adoption of the draft law. Before the second reading, there was a proposal to change these four years to three, but this did not improve the situation. Effectively, it referred to the application of the retroactive effect of the law in time, which, according to the Constitution of Ukraine, cannot be used in such cases. Therefore, MPs removed this provision; currently, it is possible to recover only assets acquired after November 28, 2019,—the date of entry into force of the law.

By the way, in one of the cases on civil forfeiture of the property of a customs officer, the SAPO prosecutor noted that some assets had signs of being unjustified, but since they were acquired before the law entered into force, a lawsuit cannot be filed.

The Main Legal Department of the Verkhovna Rada also drew attention to the unfounded competition of civil forfeiture and criminal liability for illicit enrichment. There is still an opportunity to avoid criminal liability by artificially “dividing” assets and initiating their recovery within a civil procedure, instead of criminal proceedings.

The competition of processes is not exclusively a theoretical problem. It already has a real practical manifestation in one of the civil forfeiture cases, which concerned the former deputy director of the preventive activity department of the National Police of Ukraine. In this proceeding, funds are considered both as unjustified assets in civil proceedings and as material evidence in criminal proceedings.

However, we have not found any serious fraud with the avoidance of criminal liability through civil forfeiture mechanisms.

The excessive workload on judges also threatened real implementation of the new legislative provisions since civil forfeiture cases shall be heard by the High Anti-Corruption Court. After the adoption of the law, it was predicted that the HACC would receive such a number of civil lawsuits that it would not be able to cope with, but in fact this did not happen.

There were many questions about the already mentioned standard of proof. MPs proposed to use a new standard of evidence—“preponderance of evidence,” which was not inherent in the Ukrainian legal system, and its content was not disclosed anywhere.

This could create a threat of arbitrariness on the part of law enforcement officers and judges since the issue of proving is closely related to the collection of evidence. The law did not detail these processes, which cast doubt on the legality of the civil forfeiture procedure in general because potential defendants did not have any rights during the collection of evidence. This problem, although less acute, is still relevant. The development of judicial practice, which we will cover in more detail further, is used to eliminate it.

MPs did not take all these risks into account, their overcoming turned into a task for judicial case law. Nowadays, we can state that it was successful, for the most part.

HACC case law on civil forfeiture

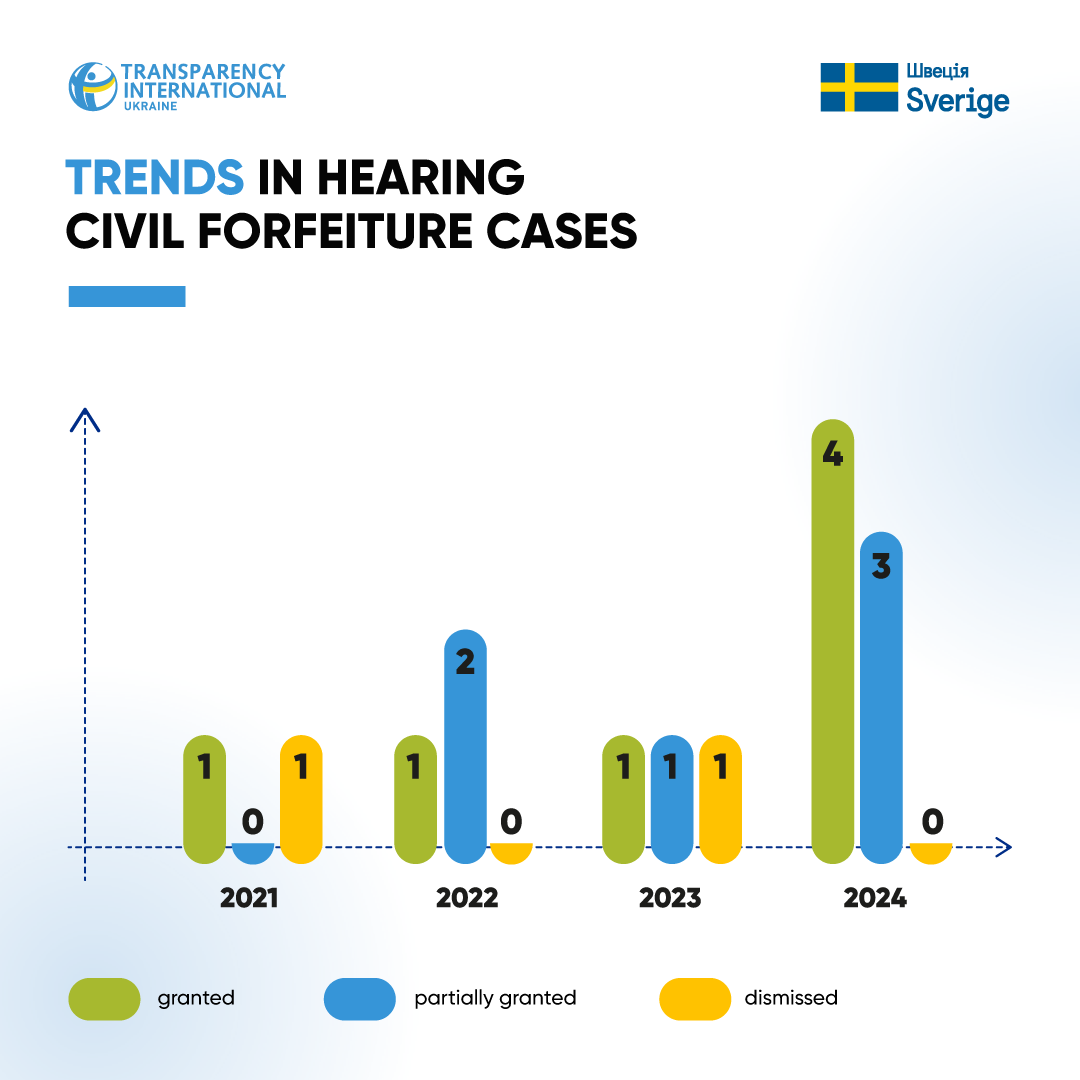

The first civil lawsuits were referred to the HACC only in 2021. As of September 2024, the court had issued 15 decisions in civil forfeiture cases. The HACC judges refused to grant the lawsuit of SAPO prosecutors twice, partially granted lawsuits 6 times, and fully granted them 7 times. Another 6 cases are pending in the first instance.

Statistics indicate that there are few lawsuits for civil forfeiture. On average, the HACC considers 3-4 such cases per year; this is despite the fact that in total, the Anti-Corruption Court hears about 50 criminal cases per year.

The hearing of civil forfeiture cases takes much less time than the hearing of other corruption proceedings. The average time for their consideration is 70 days, while criminal cases on the merits are heard much longer—more than 508 days per case.

Notably, despite the rapid process of hearing such cases, the tendencies of their frequent initiation are observed only now. This may be primarily due to the relatively recent launch of the mechanism, since the first lawsuit was referred to the court only in 2021, after the Verkhovna Rada restored the powers of the NACP, which had been recognized as unconstitutional by a well-known decision of the Constitutional Court.

It is the procedures for declaring assets and monitoring the lifestyle of officials conducted by the NACP that should be the primary sources of information about the probable facts of acquiring unjustified assets. Based on the analysis of court decisions in these cases, we see that the declarations and other materials of the NACP form the basis of the evidence base of SAPO prosecutors to prove the unjustified nature of the asset.

In addition, the number of lawsuits for civil forfeiture was clearly affected by the suspension of the declaration by officials. Therefore, restoring this obligation and the intensified verification of declarations may further increase the number of lawsuits.

In 2024, SAPO prosecutors referred several lawsuits, with record high value of assets. In particular, on May 10, the prosecutor filed a lawsuit for almost UAH 7 million regarding the recognition of the assets of the head of a territorial service center of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in the Dnipropetrovsk region as unjustified. Earlier, in March, prosecutors filed a lawsuit against the head of one of the sectors of the Kyiv customs for confiscation of more than UAH 8.6 million. The HACC has already considered and granted both of these lawsuits.

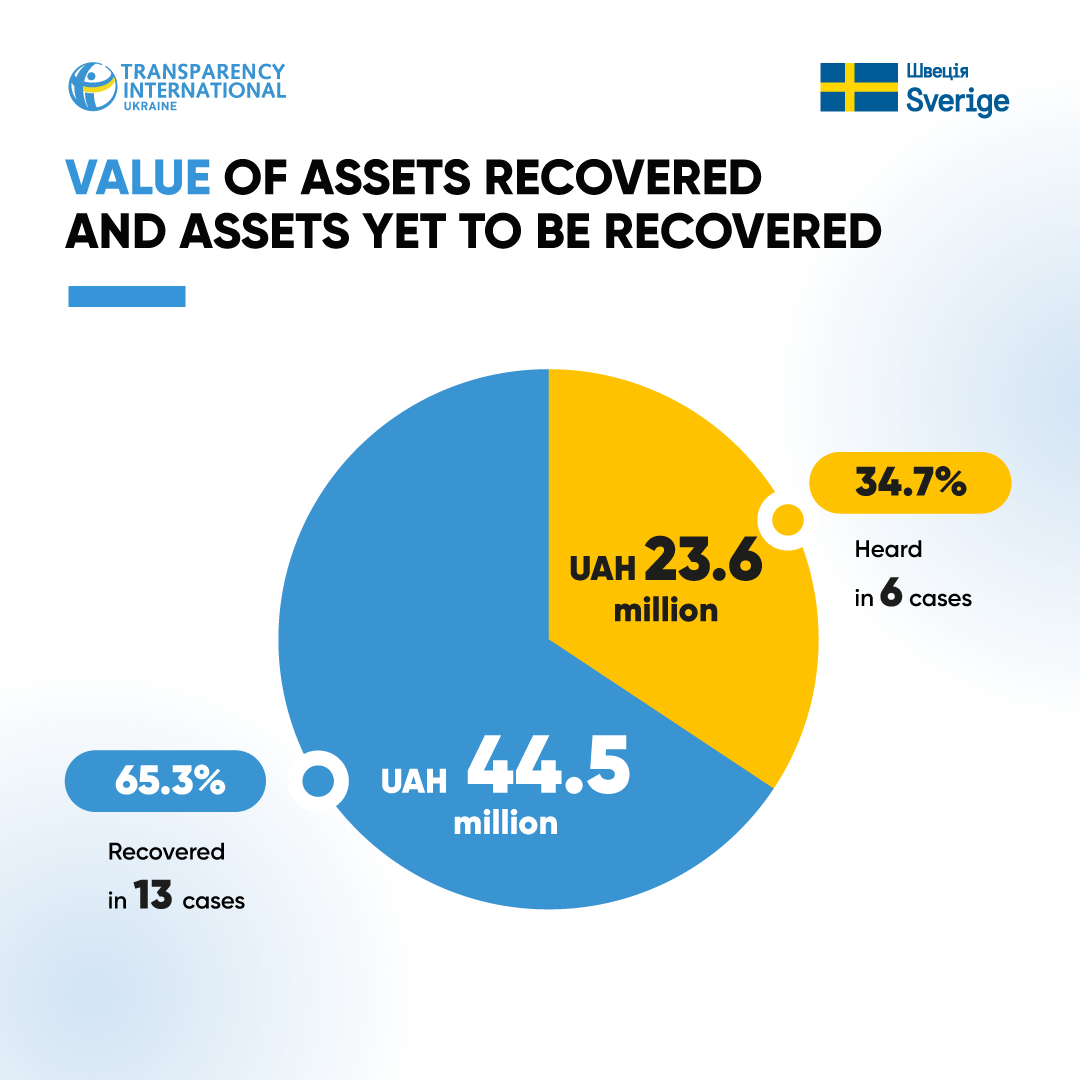

A striking indicator of the performance of the HACC in such cases is the value of confiscated assets. In more than 3 years, through the mechanism of civil forfeiture, the Anti-Corruption Court has recovered more than UAH 44.5 million in 13 positive cases for the SAPO in favor of the state.

As of September 2024, the HACC is hearing 6 cases on civil forfeiture, and the total amount of the stated lawsuits reaches UAH 23.6 million.

Most often, the SAPO requests to confiscate funds that make up the value of unreasonably acquired real estate. As of September 2024, 40 objects (land plots, apartments, houses, parking spaces) were requested to be recovered. Twice did such motions refer to the collection funds per se; 8 vehicles were requested to be recovered.

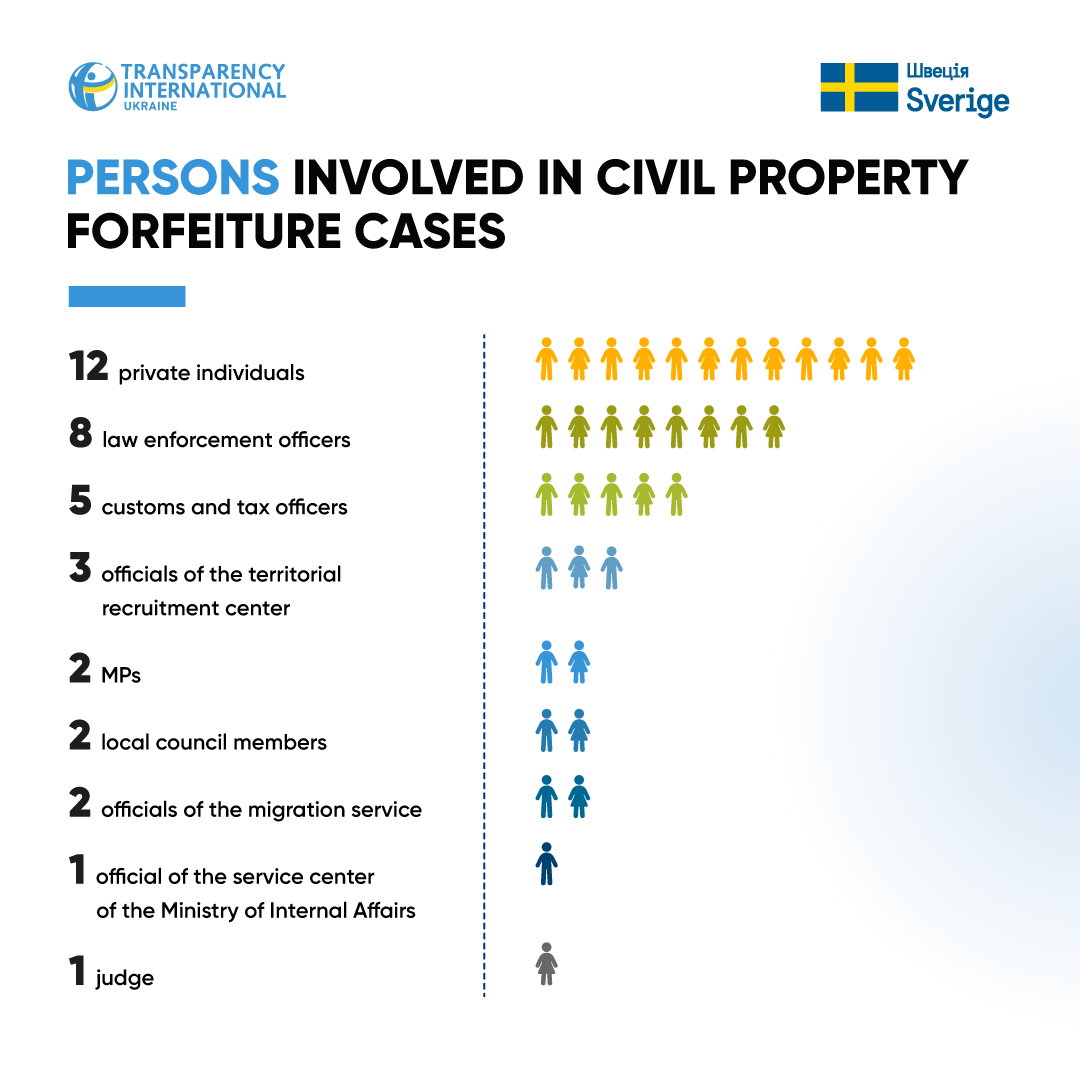

The entities from whom such property is confiscated have also been diverse. As of September 2023, the defendants in civil forfeiture cases were 8 law enforcement officers, 5 customs and tax officers, 2 MPs, 2 local council members, 2 migration service officials, 3 officials of the territorial recruitment center, 1 judge, 1 official of the service center of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, and 12 private individuals.

We can state that the number of lawsuits for civil forfeiture is increasing, and this tool gets applied to various entities. Moreover, the pace of hearing such cases is indeed quicker than that of criminal cases.

Peculiar features of hearing civil forfeiture cases

As of September 2024, 11 of the 15 decisions were appealed to the HACC Appeals Chamber: 1 decision was changed, 8 were upheld, and 2 are still pending in the appellate instance.

Although there are not so many decisions on civil forfeiture, we can already single out certain problems of this procedure.

Level of regulation of the evidence collection process is lower than in the criminal process

As a general rule, the NABU and the SAPO are engaged in the collection of evidence for civil forfeiture cases. In some cases, these functions can also be performed by the SBI and the Prosecutor General's Office, in particular when the lawsuits relate to NABU or SAPO employees.

In addition, the NACP plays an important role as well, which, in cases of detecting unjustified assets, initiates the issue of their recovery before the above-mentioned authorities.

The procedure for collecting evidence is not clearly regulated, and this problem was known when the draft law on civil forfeiture was being developed. The legislation provides for the right of the above-mentioned bodies to collect evidence through submitting requests, obtaining information from registers and other databases, as well as an opportunity to review certain information provided by various public authorities. But this does not prevent the defendants from questioning the procedure for collecting evidence by SAPO prosecutors.

Therefore, in some cases, the court did not consider the collected information due to violation of the rules for collecting evidence. In the case against Viktor Tkachenko, the deputy head of one of the departments of Odesa Customs, the court did not consider the explanations of certain individuals who had been interviewed by NABU employees. The law does not directly allow such an interview, and therefore the court cannot accept the explanations received.

This approach of the HACC brings certainty to the processes of collecting evidence, and this is, undoubtedly, a positive thing given the blurred nature of some provisions of the law.

Thus, the problem of uncertainty in the rules for collecting evidence to confirm that officials have acquired unjustified assets is solved by case law. However, to prevent different approaches to assessing the sources of evidence, it is necessary to structure the case law on these issues or to regulate them within legislation.

Assessing the value of assets, the amount of legitimate income and expenses

The key issue when hearing cases is the assessment of the value of assets compared to the legitimate incomes of officials.

Within the civil forfeiture procedure, unjustified assets, the value of which varies from UAH 1,003,500 to UAH 9,841,000 (in 2024), are recovered. Going beyond these thresholds is grounds for dismissal of the lawsuit.

The prosecutor filed a lawsuit for confiscation of part of the cost of the UAH 1.46 million apartment against the spouses, who were officials of the Novomoskovsk District Department of the National Police. In the process of hearing the case, the court recognized only UAH 922,500 as unjustified assets, that is, less than the amount established by law, and therefore dismissed the prosecutor's lawsuit to recover these funds.

By filing an appeal, the prosecutor argued that such a court refusal is unlawful because the value of unjustified assets, in her opinion, is a filter only at the stage of accepting the lawsuit for consideration. And if the court recognizes the lawsuit as justified only in part, it must still grant it and recover assets that are determined by law to be less than the established amount. However, the HACC Appeals Chamber did not agree with this position of the prosecutor.

The minimum amount of unjustified assets established by law does not apply only if it is not the assets that are confiscated, but the income from them. An example is the case of the assets belonging to the deputy director of the Department of Preventive Activities of the National Police. After the funds on his deposit accounts were recognized as unjustified, namely UAH 2,300,800 and USD 35,481, the SAPO prosecutor filed a lawsuit to recover UAH 399,070.06 and USD 314 of payments on the deposit from these funds, and the court granted it.

When assessing the amount under unjustified assets, the court calculates the difference between the maximum possible legal income and reasonable expenses. For example, in the case concerning the apartment of the head of the customs clearance department at the Horodok customs office (the Lviv Customs of the State Customs Service), the court calculated the difference between legitimate income and expenses for the purchase of real estate and vehicles. The court also considered the materials of the State Statistics Service on average total expenses per month per household (family) in different years.

Article 290 of the Civil Procedural Code of Ukraine includes wages, fees, dividends, interest, royalties, charitable assistance payments, pensions, income from the sale of property, savings, savings in foreign currency, precious metals, and other non-prohibited income.

The primary source from which calculations of legitimate income are made is the official's declarations for the periods in which the asset was acquired. To calculate them, the court adds the incomes specified in the declarations for the year of acquisition of the asset and the one before it. Monetary assets are measured considering the reporting period when the asset was acquired.

When calculating, the court does not consider those funds of the person that have not changed after the acquisition of the asset; otherwise this should be reflected in the relevant declaration. When explaining where additional funds come from, officials usually provide the court with evidence of loans, financial assistance, etc. However, the court does not always accept it, assessing the reality of such liabilities.

This was true for the case of a city council member in the Dnipropetrovsk region, who acquired a house and a land plot for UAH 2.4 million, received on loan. The court questioned the reality of the loan of UAH 2.4 million, since it took place immediately after the defendant and the lender got acquainted due to their allegedly friendly relations and without any guarantees of return of funds (surety bonds, pledge, etc.). The same was true for the case of the Odesa customs officer.

Sometimes such documents are still considered by the court and become the basis for partial granting of lawsuits. Sometimes the HACC dismisses the SAPO prosecutor's lawsuit altogether if the latter could not prove that the value of the unjustified assets of the official exceeded the threshold of UAH 1,003,500.

Thus, reasonable expenses also play an important role in the proving process. First, the court calculates the person's lawful income, from which reasonable expenses are then deducted. The result is the value of the unjustified asset.

The court shall form the amount of expenses considering the documented expenses of the person. In addition, to explain them, the HACC also assesses expenses from the perspective of common sense, when it is impossible to calculate the total household expenses. Therefore, the amount of expenses established while hearing the case does not include the undocumented expenses for food, clothing, utilities, housing, transport, healthcare, etc.

Such difficulties could be avoided if the prosecutor interviewed the potential defendant. However, there are a few caveats to this.

Firstly, the prosecutor can receive an explanation from a person by law only with their consent and only to clarify the grounds for representation in this case. That is, the prosecutor has no powers to gather testimony as evidence in a civil forfeiture case.

Secondly, such an interview may lead to the fact that potential defendants will sell or re-register a potentially unjustified asset before the lawsuit, that is, it will complicate the case. However, if the prosecutor files a lawsuit based on the results of the lifestyle monitoring, then when establishing the discrepancy between the standard of living and the income of this person, the NACP notifies them of such a fact and gives them an opportunity to provide a written explanation within ten working days.

While in public service, individuals should pay special attention to documenting both income (through the submission of e-declarations) and expenses. To improve the quality of the lawsuits filed, it is necessary to consider information about the expenses of the person, including by clarifying the position of the potential defendant. To this end, prosecutors should be granted relevant powers by law.

Form of recovering unjustified assets

Contradictory in practice was the question of the form of recovering the asset: in its value or in its kind.

The literal interpretation of Art. 292 of the Civil Procedural Code of Ukraine says that if an asset is recognized as unjustified, it should be recovered in whole or in part. However, if it is not possible to separate such a part, then its value is recovered. Similarly, the value of the asset is recovered in the case of effective impossibility to confiscate the unjustified asset, for example, when this property is no longer in the possession of the defendants.

SAPO prosecutors file lawsuits to recover the asset itself, its value, or the money spent on its acquisition. The legislation does not provide under which conditions and when it is appropriate to use a particular method of protection, but the level of interference with the rights of the defendant directly depends on the choice of such a method.

It means that over time, the value of assets may increase due to the usual market price increase or improvement.

SAPO prosecutors usually request to recover not the asset itself, but its value or part of the value at the date of acquisition (according to Art. 290, part 3 of the Civil Procedural Code of Ukraine). This approach to civil forfeiture is the most liberal and prevents accidental recovery of legitimate assets.

But the problem is that it is about collecting the amount “as of the date of acquisition,” and this allows officials to make money on market fluctuations in the price of assets (mostly real estate), which can also be considered income from an unjustified asset.

This happened in the case of the head of a Lviv Customs Department, who was charged UAH 1.86 million, that is, the cost of the apartment as of the date of its acquisition. However, as of the date of the decision, the average market value of such a three-room apartment of 103.3 square meters was more than UAH 5 million. The difference is huge—more than UAH 3 million.

But there are two cases in the case law of the HACC, where the prosecutor asked to recover the assets themselves, and not their value. One of them ended with a refusal to recognize the assets as unjustified and, accordingly, to recover them, while the other was more effective.

This second case concerned the assets of an Odesa customs officer. The court decided to confiscate, among other things, an apartment, but within its value at the time of acquisition. The Appeals Chamber changed the form of confiscation to the recovery of only the amount of money. After all, significant improvements (repairs) were carried out in the apartment, but not at the expense of unjustified assets, which the defendant proved.

Interestingly, on June 20, 2024, in the case of civil forfeiture of assets belonging to the head of the Lviv Customs Department, the Supreme Court made a significantly different conclusion. The court pointed out that the indication of the value is important for the qualification of such an asset as unjustified, and not for its recovery into the national income. Therefore, the courts do not need to indicate the value of the asset or determine a certain amount of money within which a lawsuit will be filed to recover the property. That is, it is necessary to recover not the value of the asset established as of the date of its acquisition, but the property.

6 HACC decisions to grant the prosecutor's lawsuit for the recovery of assets (other than monetary assets) relate to the recovery of their value as of the date of acquisition or recovery of the asset within a certain amount. That is, we are talking exclusively about the money spent on the acquisition of these unjustified assets.

Therefore, this conclusion of the Supreme Court contradicts the case law of the HACC and obviously puts the defendants in a much worse position, since it allows the confiscation of the asset with all its improvements and increase in value.

International standards of confiscation without a verdict interpret that in the case of mixing property, confiscation of its illegal part is allowed.

The opinion of the Supreme Court as of June 20, 2024, does not consider various situations where a legitimate asset can be mixed with an unjustified one. Therefore, this may cause a dangerous precedent for an overly repressive and indiscriminate mechanism of civil forfeiture.

But we should expect that the Supreme Court will provide a more detailed conclusion in another case, which, unfortunately, the Grand Chamber of the Supreme Court refused to hear. On October 21, the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor's Office announced that the Supreme Court concluded this case, upholding the HACC's decision as legal. However, at the time of publication, the full text of the decision had not yet been released.

In this proceeding, the prosecutor filed a lawsuit to recover not the controversial apartment itself or its value, but the funds used for the purchase. The HACC recovered a part of the value of the asset, recognized as unjustified, and the HACC AC upheld this decision.

Therefore, the Supreme Court faces important questions about the possibility:

- for the prosecutor: to file a lawsuit for the recovery of funds used to purchase unjustified assets, and not the asset itself;

- for the court: to recover the difference between the value of acquired unjustified assets and the maximum possible legal income of the official;

- the prosecutor: to file a lawsuit against another individual or legal entity (and not exclusively against an official) if the issue of recovery of assets from such persons is not brought before the court.

We hope the Supreme Court's answers are well-founded and comprehensive, guiding the practice of civil forfeiture cases in the right direction.

In our opinion, it is more rational to recover an unjustified asset rather than its value, but only in cases where no permanent improvements have been made to it for legitimate income. This will help prevent the opportunity for officials to make money on market fluctuations in the price of assets.

If it is impossible to separate a “legitimate” asset from an “unjustified” one, then it will be rational to confiscate the market value of the unjustified part. Similarly, when the defendant sold an unjustified asset, income from its sale or funds in the amount of the market value at the time of alienation should be subject to confiscation if the asset was sold free of charge or at an underestimated cost.

Establishing the link between the official and the asset

Recognizing an asset as unjustified is possible only if a link is established between it and the official. This connection can be displayed in the direct ownership of an asset by a person, the nominal ownership of another person on the behalf of the former, as well as in actions identical to the disposal of assets.

Proving this connection is one of the most difficult tasks SAPO prosecutors face.

The substantiation of such a connection is based on the testimony of witnesses (asset sellers, nominal owners, relatives), information about telephone connections of officials, video recordings of public spaces, chats from messengers, etc.

When assessing the fact of acquiring unjustified assets, the court is guided by the standard of proof “preponderance of evidence.” It is the logical errors in the positions of the parties that become key benchmarks for judges when recognizing a fact as more likely.

For example, in the well-known case of the “pulp pit,” former MP Illia Kyva tried to prove that he owned the property legally, and the sale of the asset, for which he received unjustified UAH 1.25 million, was committed fraudulently, without his knowledge. But the judges critically assessed this statement and questioned the reality of the transaction of leasing the pulp pit because the company that rented it did not use it.

Describing the link between the apartment and two parking spaces with the former head of the Odesa customs, the court also found inconsistencies in his statements. The defendant stated that the property was purchased by his mother, a retiree, who had lived there since 2020. However, from the interrogation of the seller and the tracking of telephone connections, it was established that the defendant himself was engaged in the search for real estate and its registration. In addition, from 2020 to 2022, the apartment was under renovation, which would not allow the mother to live there. The court also questioned the fact that, having no cars, the defendant's mother purchased two parking spaces. In this case, the HACC established that the mother was only the nominal owner of the property, and the actual user was the official himself.

The most difficult issue in this category of cases is ensuring the rights of third parties, actual owners of assets, which the prosecutor considers unjustified.

Practice shows that one of the most common ways to disguise unjustified assets of officials is their nominal ownership by a person who is not an official. Under these conditions, the court must analyze the financial capacity of both to acquire the controversial asset.

In one of the cases, the defendant did not deny the acquisition of a three-room apartment in Lviv as a gift from her parents. The court concluded that her financial resources and her parents' resources would not be enough to purchase an apartment. The connection between the official and the asset, according to the court, was expressed in the “direct method of acquiring assets, which at the same time is indirect” because the gifting of the apartment took place the day after the purchase by the mother. The Appeals Chamber agreed with this wording and all the consequences derived from it. This was also confirmed by the Supreme Court.

However, such categories of cases raise many questions because depending on the type of connection with the asset, the court decides whose property status is subject to assessment. At the same time, the assessment of the financial capacity of third parties is not directly provided for by law and, although it is not key in confirming the ownership of the controversial asset by the official, it still becomes a crucial circumstance in such cases.

The legitimacy of assessing the financial position of third parties cannot be questioned. At the same time, the court is often limited in its ability to verify the possibility for a third party to acquire the controversial asset because this person is not obliged to declare the assets. Therefore, the law could clearly regulate that the receipt of information by the court from the formal owner of the asset about their income will not be an interference with privacy if the prosecutor has proved the connection of this person with the official.

Enforcement of HACC decisions

As of the first half of 2024, the HACC issued 8 enforcement orders for the recovery of unjustified assets from 9 persons. 2 out of 9 enforcement proceedings have been completed. 7 proceedings are still pending.

Our study once again proves that the lion's share of problems of legal proceedings concerns the enforcement of decisions. We have already studied the enforcement of HACC verdicts with confiscation, and its effectiveness leaves much to be desired. A similar situation is observed in this case. The search for the property of dishonest officials who skillfully disguise it becomes a serious obstacle to the recovery of unjustified assets into the state income for their legal distribution.

The average duration of open enforcement proceedings is almost a year. Notably, the first HACC decision on civil forfeiture in the case of the “pulp pit” has not yet been enforced, although former MP Kyva has already died. Enforcement proceedings were opened on December 13, 2021, and as of September 2024, in accordance with the Automated System of Enforcement Proceedings, they were not completed.

Interim relief in the form of seizing the controversial property is used quite often, but not always.

For example, in the “pulp pit” case, such measures as the seizure of funds (unjustified income from the lease of real estate) were not applied. The same situation is with the couple of Kharkiv tax officials, who acquired an unjustified house and a land plot. Interim relief measures were not applied to this property or funds.

The HACC statistics and the court register allow observing a tendency to increase the number of applications for interim relief. Thus, in 2021, 2022, prosecutors did not file any such application; in 2023, they filed five, and in 2024, there were six such applications.

That is, if these assets are not seized, for example, within criminal proceedings, the lack of interim relief may cause serious obstacles to the confiscation of unjustified assets or their value, given the workload and related problems of the executive service.

However, the fate of open enforcement proceedings, where the controversial assets were seized, remains in question; the decisions on their recovery entered into force, but the assets were never fully confiscated.

The executive service does not provide information on how it enforces certain decisions of the HACC, so it is currently impossible to find out for sure what becomes an obstacle to replenishing the treasury with unjustified assets. We can state that the problem of non-enforcement or poor-quality enforcement of HACC court decisions on asset recovery can turn into a systemic one.

Conclusions

The tool of recognizing assets as unjustified and recovering them into the national income (civil forfeiture) is becoming widespread in Ukraine. This is evidenced by the increase in the number of SAPO lawsuits against officials in this regard.

However, there are certain procedural problems that can be solved either by changes in legislation or by the development of case law. Unfortunately, the current state of enforcement of decisions on civil forfeiture is difficult to track, which requires increased public attention to this stage.

The analyzed case law of the HACC and the Supreme Court in the issue of civil forfeiture allows formulating the key features inherent in these processes, as well as to offer opportunities for their development.

- Civil forfeiture cases are marked by lower regulation of the evidence collection process compared to criminal proceedings. The problem of uncertainty in the rules for collecting evidence to confirm the acquisition of unjustified assets by officials is solved by case law. However, to prevent different approaches to assessing sources of evidence, the case law needs to be structured.

- Questions remain in terms of assessment of the value of assets, the amount of legitimate income and expenses. While in public service, individuals should pay special attention to documenting both their own income (through the submission of e-declarations) and expenses. To improve the quality of the lawsuits filed, the prosecutor should be allowed to conduct a preliminary interview of the potential defendant on expenses and income at the legislative level.

- Undefined forms of recovery of unjustified assets. Confiscation of an asset with improvements is possible only if the prosecutor has proved the unjustified nature not only of the asset, but also of the improvements made (in particular, the funds used for them). In the case when the defendant has already sold an unjustified asset before confiscation, it is necessary to recover income from its sale or, if the asset was sold free of charge or at a lower cost, the market value at the time of alienation. But as a general rule, it is necessary to confiscate the unjustified asset itself, and not its value at the date of acquisition.

- Difficulties in establishing the connection between the official and the asset are still relevant. The legitimacy of assessing the financial position of third parties cannot be questioned. However, the court often cannot verify the possibility of a third party to acquire the controversial asset, since they are not obliged to declare the assets. Therefore, the law should clearly regulate that the receipt of information by the court from the formal owner of the asset about their income will not be an interference with privacy if the prosecutor has proved the connection of this person with the official.

- There is no public communication on the enforcement of decisions on civil forfeiture. The executive service does not provide information on how it enforces certain decisions of the HACC, so it is currently impossible to know for sure what becomes an obstacle to replenishing the treasury with unjustified assets. The issue of non-enforcement or poor-quality enforcement of HACC court decisions on material recovery of assets may turn into a systemic one.

In the future, the tool of civil forfeiture might still develop, in particular in terms of expanding the grounds for its application. The Asset Recovery Strategy, approved in August 2023, proposes to expand the application of confiscation of unjustified assets. However, based on the analysis of the ECHR decision in the case of Gogitidze and Others v. Georgia, we reiterate that such measures should be implemented in compliance with human rights standards.

In addition, the tool of civil forfeiture should extend to assets acquired by criminal organizations if they cannot be recovered through criminal proceedings. In April 2024, the EU adopted Directive 2024/1260 on asset recovery and confiscation, which introduced such a measure. At the same time, it is necessary to consider such factors as the incommensurability of the value of the property with the legitimate income of the owner, the lack of a legitimate source, and the owner's connection to criminal organizations. Considering these new European provisions and expanding civil forfeiture are important factors because of the need to harmonize Ukrainian legislation with EU law.

Contributors

Kateryna Ryzhenko, Deputy Executive Director for Legal Affairs, Transparency International Ukraine

Authors of the study: Pavlo Demchuk, Legal Advisor at Transparency International Ukraine; Andrii Tkachuk, Junior Legal Advisor at Transparency International Ukraine.

This publication was prepared by Transparency International Ukraine with the financial support of Sweden.